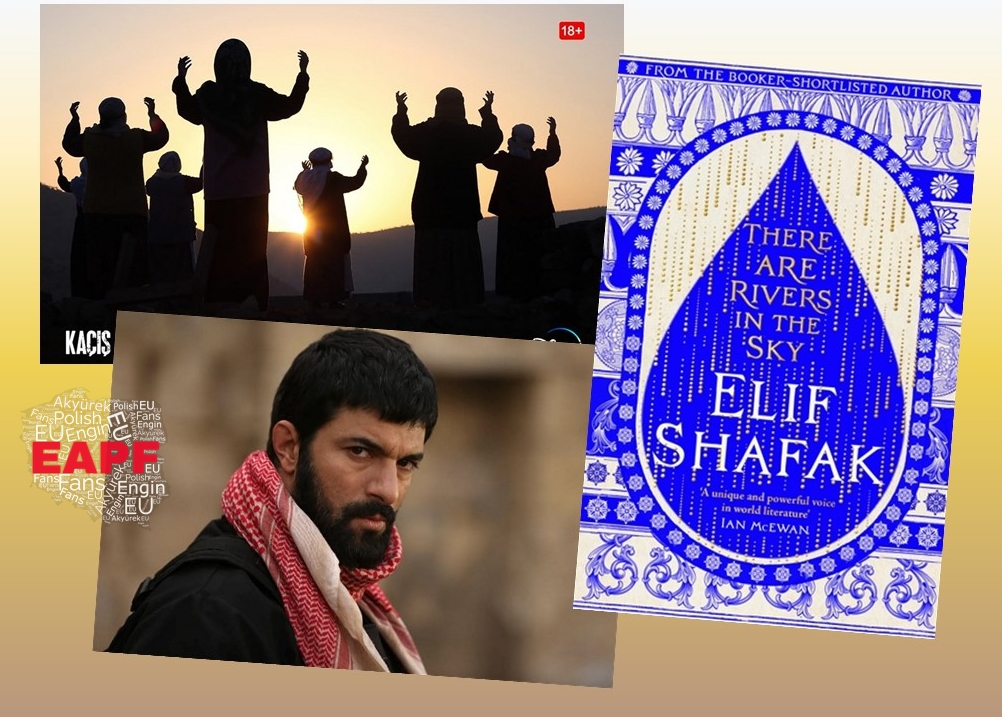

Kacis, Shafak and the Yazidis - a note on the novel "There Are Rivers In The Sky"

The latest picture shared by Sinasi Serce reminded me of Kacis, Kacis reminded me of the Yazidis, and the Yazidis of the latest book by Elif Shafak - There Are Rivers in the Sky.”