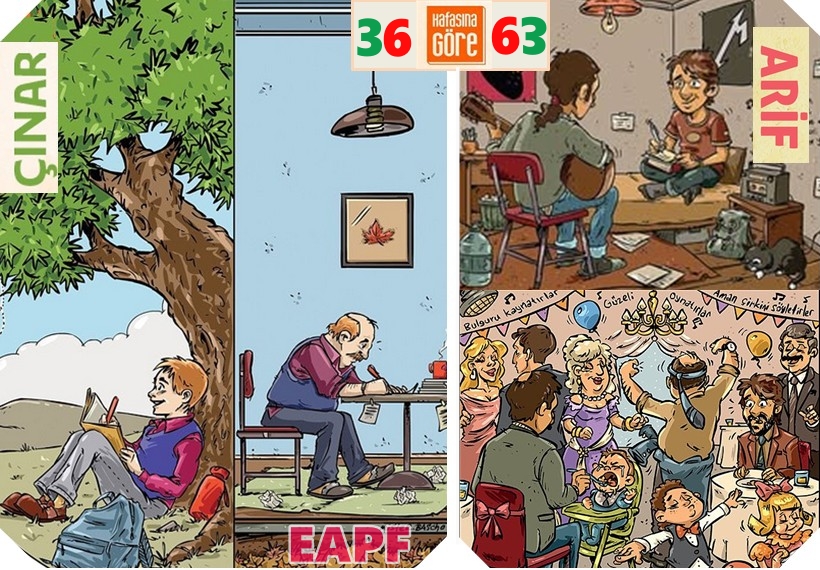

Memory, Fiction, Responsibility – Two Faces of Writing in Engin Akyürek’s Short Stories “Arif” and “Çınar”

“Arif” and “Çınar” – two short stories by Engin Akyürek with brief, one-word titles. Moreover, Çınar is story number 36, while Arif is number 63, as if their very numbering suggested that they should be read together. No wonder, then, that reading “Arif” immediately reminded me of the earlier “Çınar” (The Plane Tree), whose content seems deceptively similar. What links the two texts is a reflection on writing and its ethical boundaries. In both, the main characters are writers who unexpectedly achieve success by telling the stories of real people they know well. In both cases, they do so without the knowledge or consent of those involved—yet the people described recognize themselves in the texts. Thus, both stories focus on the relationship between reality and literary transformation, and raise a fundamental question about authorial responsibility: does a writer have the right to use someone else’s life in their work?

And yet, the similarities end here.

In “Çınar” we meet Mehmet Nuri, who has been writing since childhood. For him, literature is not a profession but a way of existing—almost a “twin brother.” Despite this, at one point he falls into a creative crisis and loses faith in his own abilities. It is only the encounter with Selim, an old school friend, and a letter from him, that restores his inspiration.

In “Arif”, the narrator is also a writer, but his relationship with writing is completely different. It is not a lifelong passion but rather a coincidence: instead of the planned career as an engineer, his path changed when one of his stories won a competition. From that moment on, he has never lacked inspiration, and he treats writing more as the outcome of fate than as an inner necessity.

Both protagonists use literature to transform reality, but they do so in very different ways.

Mehmet Nuri in “Çınar” writes about Selim’s family, focusing on the figure of his father. He keeps the real names, but the plot itself is a product of his imagination—including the alteration of the father’s character traits. The story created is therefore not a faithful record but a reinterpretation of the past. Surprisingly, Selim receives it positively. In his letter, he thanks for the book, writing: “Thank you for reminding me how much I needed this [=the contact with my family].”

For him, fiction turns out to be more than just a literary game – it becomes a trigger for reflection on his own story and family relationships: “I really wish my family’s story looked the way you presented it.”

In “Arif” the situation is the reverse. The narrator tells the true story of his friend and, in a way, mentor, Metin, changing only his name. What is more, the very idea of using the story came from Metin himself, who once suggested in conversation that his life could serve as material for fiction. The narrator thus appropriates not only private memories but also someone else’s idea. He publishes the story without asking for permission or giving warning. Metin’s reaction is cold—he withdraws from the friendship, leaving the narrator alone with his guilt.

The two stories therefore present two opposing models of literary transformation of reality. In “Arif”, factual truth is preserved, but the lack of consent and empathy leads to pain and the loss of a bond. In “Çınar”, factual truth is altered, yet this produces a story that moves, soothes, and opens a space for reconciliation with the past.

Conclusion – Two Faces of Writing

In “Çınar”, the author asks: is the role of literature to document reality, or to interpret it? Selim’s letter provides an answer—it is not about faithfully reproducing facts, but about creating a story that helps one understand oneself, forgive, and give meaning to the past. Fiction, though detached from literal reality, can be ethical, empathetic, and healing if it springs from sensitivity and genuine respect. It can open hearts, revive memories, and mend relationships.

“Arif”, on the other hand, warns that writing about another person is always an intrusion into their privacy, and without consent and empathy it may wound. Even the best intentions are not enough if attentiveness is missing.

To sum it up in a single sentence: “Çınar” shows that writing can be a bridge between people and their past, while “Arif” shows that it can become a wall if empathy and sensitivity toward the person described are lacking.